1 - Theosophical Society was

established with apolitical and non-violent peace- building policies.

Firstly, the early Theosophical Society was

established with apolitical and non-violent peace-building policies.

Theosophists

are of necessity the friends of all movements in the world, whether

intellectual or simply practical, for the amelioration of the condition of

mankind. We are the friends of all those who fight against drunkenness, against

cruelty to animals, against injustice to women, against corruption in society

or in government, although we do not meddle in politics. We are the friends of

those who exercise practical charity, who seek to lift a little of the

tremendous weight of misery that is crushing down the poor. (Letter I — 1888

Second Annual Convention — April 22-23, CW 9:247)

In the neo-theosophical period, Annie

Besant makes a conspicuous exception to the apolitical policy (motivated by esoteric

reasons) when she becomes president of the Indian National Congress.

Personally, I think she had an overall positive impact, however, since there is

only one full book (Isaac Lubelsky: Celestial India. Madame Blavatsky and the Birth of Indian Nationalism, Sheffield (UK)/Oaksville (US): Equinox 2012,) (with several articles as well) on the role of

the Theosophical Society in India’s independence movement. It's not bad, but a lot more could be written on the subject. The recent Imagining the East: The Early Theosophical Society (Oxford, 2020) adds some much-needed research and discussion.

My personal view is that the original

policies entail that a writer, lecturer or administrator in a theosophical

organization should refrain from publicly taking active political roles and

expressing partisan political views.

2- Tendency in the mass media

to consider everything in terms of conservative or liberal political leanings.

One problem related to misconceptions, is a marked tendency in the mass media

to consider everything in terms of conservative or liberal political leanings. In

Blavatsky’s case, she gets identified, for better or worse, in right wing and

left wing camps. For example, both Gandhi and certain Nazis have been considered to be

influenced by theosophy. Also, she is targeted in both globalist woke and antifa racist conspiracy theories. To me, that

indicates her views encompass something more complex than simple right or left

wing categories.

In contemporary times, some researchers express surprise to find that certain groups or

protagonists don’t fit into comfortable left wing hippie or right

wing white collar political categories, whereas the alternative

spiritual movement has always been characterized by an individualist ‘salad

bar’ mix of diverse beliefs and practices, so one could ask if that categorizing

tendency is not inherently inadequate. There is also the spiritual-materialist opposition, so a political conflict often involves complex four-way tensions between the spiritual left, the materialist left, the spiritual right, and the materialist right.

3- Occultism and Fascism

connections

With this part we reach the crux of the problem, since most of the

recent volatile political situations with occult connections come from

right-wing factions, related to a general upswing in right-wing political

movements. It’s understandable that there is serious concern with this

situation and I can see how the greater focus on this problem has valid

motivations. The gist of my observations, besides arguing that Blavatsky’s name

need not be dragged through the mud in all this, is to note how the current

coverage of the situation can be counter-productive, mainly due to

over-reliance on outdated political assumptions that do not have the nuances

needed to fully explain the nature of the problem.

I think the main problem is that the current political

situation might have augmented an anti-esoteric stance in political studies. Some esoteric historians have complained of this (Review of Kurlander's Hitler's Monsters) The result tends

to leave the discourse conditioned by the unfortunate agenda set by The Morning of the Magicians. For example, the promotion of the Kurlander book seemed to capitalize on

media sensationalism, which tended to increase misconceptions related to

conspiracy theories, rather than to diminish them. It seems that even Peter

Staudenmaier may have noticed the problem and felt the need write a corrective (The Nazis as occult masters? It’s a good story but not history). Despite much solid effort in the last twenty years in the area of esoteric history, I would say there is still a lot that we simply do not know, and I

think we are far from coming to terms with the legacy of the second world war (For example, a more accurate understanding of Adolf Eichmann only emerged in the mainstream less than ten years ago, thanks to the exceptional historical research of Bettina Stangneth). Progress

has been made, but there’s still work to be done on integrating esoteric

history into mainstream history. Additionally, I haven’t seen much historical

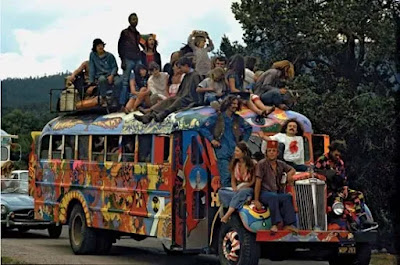

research of the considerable influence of the theosophical movement on the

1960s counter-culture movement, which I think could open up a wider field of

understanding into today’s situation (A lot of that discourse is influenced by Lopez' Prisoners of Shangri-La, which is unsatisfactory to me. I don't know if something better has been written yet).

'It would be

misleading, however, to regard occultism as a generally leftwing, liberal, or

progressive field. Its heterogeneity makes any generalisation impossible.

Right-wing tendencies in the form of racism, anti-Semitism, or nationalism

surged especially at the beginning of the twentieth century. This was a

reflection of broader tendencies within European culture and politics, from

which occultism – and this is the crucial point here – was not isolated. Quite

the contrary, the many shades of occultism formed a prominent and integral part

of avant-garde culture across Europe, and it

is not surprising that they continued to influence especially the most radical

political tendencies of its time. Racism, antisemitism, and related sentiments

had always been commonplace across the left side of the political spectrum,

too, but they were especially radicalised within the identity politics of

rightwing movements. At this point, we simply lack the research to understand

the historical development of politics within these contexts, their obvious

relevance notwithstanding. This especially applies to a comparative perspective

that takes into account the different national contexts, particularly in the

period after World War I.' (229)

'In addition

to this lack of scholarship on the entanglement of esotericism and fascism or

National Socialism, there is a general disinterest in the history of the left

side of the political spectrum. Our knowledge of this milieu, which had been

thriving in the decades around 1900, is especially limited in the German

context, firstly due to the focus on “Nazi occultism,” and secondly, as a

consequence of the far-reaching eradication of political opponents in the Third

Reich. There is, however, valuable scholarship on Russia

and the Soviet Union demonstrating the

relevance of esotericism in Communism. Certainly,

occultism cannot simply be placed on one side of the political spectrum but has

a much more complex history than is often assumed.' (231) (Doesn't Occultism Lead Straight to Fascism? Hermes Explains Thirty Questions about Western Esotericism Amsterdam

University Press 2019)

Recently, scholars in the field of archaeology have

decided to be more vocal in opposing right-wing alternative science conspiracy

theory excesses related to QAnon and the Starseed movements. (Believe in Atlantis?) As with

the Kurlander case, well-intentioned no doubt, but the actual gist of their

arguments about problematic colonialist-influenced sources (which has existed in

the scholarship since the early 1990s, I believe) have been convincingly questioned. (Kenneth Feder is failing on Atlantis. Thorwald C. Franke) Here again, I find that the approach used for the mass media

coverage of such a volatile and sensitive topic creates a sensationalistic

atmosphere that is more alarmist than informative. Julian Strube has written a

recent study, that indicates that the problem is more complex and nuanced than what

has been conveyed in the mass media coverage:

'Moving towards a more complex understanding of esotericism, but also of

related subjects such as religion or “Western culture,” means exploring the

ways in which the history of colonialism is more nuanced than a unilateral act

of appropriation, as Theosophy serves to illustrate. Identities across the

globe, even within the colonial framework characterized by power asymmetries,

have formed through a complex dependency on, and interactions with, the

perceived other. It is crucial to take that “other” into full account, to

investigate it in its own right, specifically if it is subaltern, rather than

delegating it to the margins. The case of “Western esotericism” demonstrates

that these historical complexities can only be grasped through a decentering of

research from its supposed European core.' (Theosophy, Race, & the Study of Esotericism Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 89, Issue 4,

December 2021, Pages 1180–1189)

On a personal level, among my theosophical acquaintances, I have not

found a case of strong right-wing concentration. Rather I have encountered

Theosophists who freely express their political views across a wide political

spectrum, including far left, far right and sadly, I must confess, millenialist

conspiracy theories and even fascist, neo-nazi beliefs (which I directly and publicly object to, when I can).

My own perception is that there is an alternative spiritual demographic

that has been present since the beginning of the twentieth century and that

mainstream historians have had difficulty in perceiving it and quantifying it

adequately. Moreover, traces of occult groups within a political movement

could simply be a sign of politicians noticing a significant demographic and

catering to them to obtain their vote, like they do with any other demographic

group, and using some of their ideas that seem useful to them for propaganda

purposes, without necessarily identifying with them. Politics make strange

bedfellows indeed.

4- Christianity

One point that seems clear enough to me in looking at the major cases

of theosophy influence in politics today, is that it is more akin to a 20th

century neo-theosophy form, and more specifically forms of Christian

neotheosophy or traditionalism. My view is that centuries of ingrained Christian

superstitions and attitudes will take time to change. Blavatsky was dealing with

problems with scientific thought that was still moving away from making research

conform to what was understood as Biblical chronology and was living in a world

where dominant forms of Christianity seemed to be more akin to the rigid,

conservative nature of fundamentalist Christianity.

Moreover, she was working

in an environment where Christianity was dominant in society and showed few obvious signs of decreasing, although scientific thinking was making headway as the main guiding authority. It was only in the twentieth century that

Christianity began a noticeable massive decline and dealing with the loss of stable social values,

albeit rigid, outdated and superstitious, that this entails is still a

relatively new process.

It seems that the theosophical movement is still too new for many, and

the tendency to fall back on the old ingrained Christian attitudes prevails, even though it is mixing in new

forms. So what were seeing in politics is perhaps less an emergence of new

beliefs, but rather a persistence of a fading conservative Christian mentality

with an immature theosophically-influenced covering. A lot of the new age millenialist

currents seem to be based on modified biblical apocalyptic beliefs. At the same

time, the alternative spirituality movement has grown tremendously since Blavatsky’s

time. Time will tell if it continues to thrive while conservative Christian forms

and attitudes continue to decline. The decline of Christianity would probably have been even more pronounced had it not been for televangelism, the considerable success of missionary movements in the twentieth century, and the Pentecostal movement, which itself has mystical tendencies.

5- Repressive,

dismissive attitudes

An underlying theme of this post has been related to problems of

underestimating the role of spiritual beliefs in society. As has been seen in recent

times, because people have strange esoteric beliefs does not mean that they aren’t capable of taking

concerted organized action within socio-political structures; they are active

agents in society and their numbers are considerable. Moreover, it would seem that forms of distorted, diluted, neo/pseudo Theosophy

have motivational power. Apparently, they can give people a sense of greater

direction, healthier living, clearer purpose than the options currently available

to them.

A lot of times, a hyper-mystical

new age attitude indicates a kind of intellectual dissociation that is accompanied with

very materialistic behaviours and pursuits, and often such people can be very competent in mundane affairs. In

certain cases, complicated lawsuits resulted in positive results for religious

freedom, for example, in the Guy and Edna Ballard case, the Supreme Court in

a 5-4 landmark decision held that the question of whether the Ballards believed

their religious claims should not have been submitted to the jury, and remanded

the case back to the Ninth Circuit, which affirmed the fraud conviction.

Interpreting this decision, the Ninth Circuit later found that the Court did

not go so far as to hold that "the validity or veracity of a religious

doctrine cannot be inquired into by a Federal Court." (Cohen

v. United States, 297 F.2d 760 (1962)

Certain tendencies that I’ve noticed that tend to categorize them

strictly in terms of social or intellectual deviance, to sensationalize or

exaggerate their potential danger, excessively focusing on extreme cases

without considering the many peaceful examples can lead to dehumanizing,

scapegoating, marginalizing, and ostracizing attitudes that are ultimately

forms of repression. From a historical perspective, has repression ever worked? Despite

centuries of violent repressions, esoteric movements keep on returning. Blunt

repression is not considered effective at a psychological level; it only

creates a pressure cooker situation of pent-up energy that will re-emerge in

full force. Perhaps it is similar with history. Gary Lachman has written an

interesting recent article on the question of the relation of psychology and

political repression :

'What

does this mean? It may mean that the magical, mythical, spiritual side of the

psyche, that the west has repressed for some time now and which, even with all

the New Age bells and whistles, it still hasn’t integrated in any serious way

into its conscious outlook, is popping up in some unlikely and inconvenient

places. Does this mean that Putin and a revived Holy Russia are the remedy, a

means for the west to regain its soul? No. But it may mean that we need to

throw more light and awareness on a side of the mind and ourselves we have

ignored for too long. Otherwise it will remain a region where the far-right

meet the far-out, leaving we enlightened ones in the dark.' (The Return of the Dark Side)

PS- For a more systematic essay on this question see:

Wouter J. Hanegraaff Esotericism & Democracy: Some Clarifications